- Home

- Jackson Katz

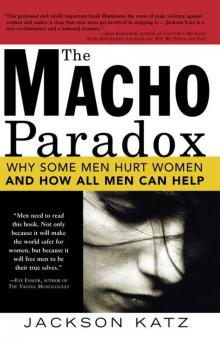

Macho Paradox: Why Some Men Hurt Women and and How All Men Can Help Page 2

Macho Paradox: Why Some Men Hurt Women and and How All Men Can Help Read online

Page 2

For the past two decades, I’ve been part of a growing movement of men, in North America and around the world, whose aim is to reduce violence against women by focusing on those aspects of male culture—especially male-peer culture—that provide active or tacit support for some men’s abusive behavior. This movement is racially and ethnically diverse, and it brings together men from both privileged and poor communities, and everyone in between. This is challenging work on many levels, and no one should expect rapid results. For example, there is no way to gloss over some of the race, class, and sexual orientation divisions between and among us men. It is also true that it takes time to change social norms that are so deeply rooted in structures of gender and power. Even so, there is room for optimism. We’ve had our successes: there are arguably more men today who are actively confronting violence against women than at any time in human history.

Make no mistake. Women blazed the trail that we are riding down. Men are in the position to do this work precisely because of the great leadership of women. The battered women’s and rape crisis movements and their allies in local, state, and federal government have accomplished a phenomenal amount over the past generation. Public awareness about violence against women is at an all-time high. The level of services available today for female victims and survivors of men’s violence is—while not yet adequate—nonetheless historically unprecedented.

There was some good news in 2005. A Department of Justice report showed that family violence declined by about half from 1993 to 2002, similar to the overall drop in violent crime during the past decade. But encouraging as it was, the study had its limitations. For example, crime between current or former boyfriends and girlfriends was not considered “family” violence. And the study did not include sexual violence. Still, we can cheer the success of our ongoing efforts but remain clear that our society still has a very long way to go in preventing perpetration. In the United States, we continue to produce hundreds of thousands of physically and emotionally abusive—and sexually dangerous—boys and men each year. Millions more men participate in sexist behaviors on a continuum that ranges from mildly objectifying women to literally enslaving them in human trafficking syndicates. We can provide services to the female victims of these men until the cows come home. We can toughen enforcement of rape, domestic-violence, and stalking laws, and arrest and incarcerate even more men than we do currently; but this is all reactive and after the fact. It is essentially an admission of failure.

What I am proposing in this book is that we adopt a much more ambitious approach. If we are going to bring down dramatically the rates of violence against women—not just at the margins—we will need a far-reaching cultural revolution. At its heart, this revolution must be about changing the sexist social norms in male culture, from the elementary school playground to the common room in retirement communities—and every locker room, pool hall, and boardroom in between. For us to have any hope of achieving historic reductions in incidents of violence against women, at a minimum we will need to dream big and act boldy. It almost goes without saying that we will need the help of a lot more men—at all levels of power and influence—than are currently involved. Obviously we have our work cut out for us. As a measure of just how far we have to go, consider that in spite of the misogyny and sexist brutality all around us, millions of non-violent men today fail to see gender violence as their issue. “I’m a good guy,” they will say. “This isn’t my problem.”

For years, women of every conceivable ethnic, racial, and religious background have been trying to get men around them—and men in power—to do more about violence against women. They have asked nicely and they have demanded angrily. Some women have done this on a one-to-one basis with boyfriends and husbands, fathers and sons. They have patiently explained to the men they care about how much they—and all women—have been harmed by men’s violence. Others have gone public with their grievances. They have committed, in Gloria Steinem’s memorable phrase, “outrageous acts and everyday rebellions.” They have written songs and slam poetry. They have produced brilliant academic research. They have made connections between racism and sexism. They have organized speak-outs on college campuses, and in communities large and small. They have marched. They have advocated for legal and political reform at the state and national level. On both a micro and a macro level, women in this era have successfully broken through the historical silence about violence against women and found their voice—here in the U.S. and around the world.

Yet even with all of these achievements, women continue to face an uphill struggle in trying to make meaningful inroads into male culture. Their goal has not been simply to get men to listen to women’s stories and truly hear them—although that is a critical first step. The truly vexing challenge has been getting men to actually go out and do something about the problem, in the form of educating and organizing other men in numbers great enough to prompt a real cultural shift. Some activist women—even those who have had great faith in men as allies—have been beating their heads against the wall for a long time, and are frankly burned out on the effort. I know this because I have been working with many of these women for a long time. They are my colleagues and friends.

My work is dedicated to getting more men to take on the issue of violence against women, and thus to build on what women have achieved. The area that I focus on is not law enforcement or offender treatment, but the prevention of sexual and domestic violence and all their related social pathologies—including violence against children. To do this, I and other men here and around the world have been trying to get our fellow men to see that this problem is not just personal for a small number of men who happen to have been touched by the issue. We try to show them that it is personal for them, too. For all of us. We talk about men not only as perpetrators but as victims. We try to show them that violence by men against each other—from simple assaults to gay-bashing—is linked to the same structures of gender and power that produce so much men’s violence against women.

We also make it clear that these issues are not just personal, to be dealt with as private family matters. They are political as well, with repercussions that reverberate throughout our lives and communities in all sorts of meaningful and disturbing ways. For example, according to a 2003 report by the U.S. Conference of Mayors, domestic violence was a primary cause of homelessness in almost half of the twenty-five cities surveyed. And worldwide, sexual coercion and other abusive behavior by men plays an important role in the transmission of HIV/AIDS.

Nonetheless, convincing other men to make gender violence issues a priority is not an easy sell. Sometimes when men engage with other men in this area, we need to begin by reassuring them that men of character and conscience need not flee in terror when they hear the words “sexism,” “rape,” or “domestic violence.” However cynical it sounds, sometimes we need to convince them that they actually have a self-interest in taking on these topics; or at the very least, that men have something very valuable to learn not only about women but also about themselves.

There is no point in being naïve about why women have had such a difficult time convincing men to make violence against women a men’s issue. In spite of significant social change in recent decades, men continue to grow up with, and are socialized into, a deeply misogynistic, male-dominated culture, where violence against women—from the subtle to the homicidal—is disturbingly common. It’s normal. And precisely because the mistreatment of women is such a pervasive characteristic of our patriarchal culture, most men, to a greater or lesser extent, have played a role in its perpetuation. This gives us a strong incentive to avert our eyes.

Women, of course, have also been socialized into this misogynistic culture. Some of them resist and fight back. In fact, women’s ongoing resistance to their subordinate status is one of the most momentous developments in human civilization over the past two centuries. Just the same, plenty of women show little appetite for delving deeply into the cultural roots of sexist

violence. It’s much less daunting simply to blame “sick” individuals for the problem. You hear women explaining away men’s bad behavior as the result of individual pathology all the time: “Oh, he just had a bad childhood,” or “He’s an angry drunk. The booze gets to him. He’s never been able to handle it.”

But regardless of how difficult it can be to show some women that violence against women is a social problem that runs deeper than the abusive behavior of individual men, it is still much easier to convince women that dramatic change is in their best interest than it is to convince men. In fact, many people would argue that, since men are the dominant sex and violence serves to reinforce this dominance, that it is not in men’s best interests to reduce violence against women, and that the very attempt to enlist a critical mass of men in this effort amounts to a fool’s errand.

For those of us who reject this line of reasoning, the big question then is how do we reach men? We know we’re not going to transform, overnight or over many decades, certain structures of male power and privilege that have developed over thousands of years. Nevertheless, how are we going to bring more men—many more men—into a conversation about sexism and violence against women? And how are we going to do this without turning them off, without berating them, without blaming them for centuries of sexist oppression? Moreover, how are we going to move beyond talk and get substantial numbers of men to partner with women in reducing men’s violence, instead of working against them in some sort of fruitless and counterproductive gender struggle?

That is the $64,000 question in the growing field of gender-violence prevention in the first decade of the twenty-first century: how to get more men to stand up and be counted. Esta Soler, the executive director of the Family Violence Prevention Fund and an influential leader in the domestic-violence movement, says that activating men is “the next frontier” in the women-led movement. “In the end,” she says, “we cannot change society unless we put more men at the table, amplify men’s voices in the debate, enlist men to help change social norms on the issue, and convince men to teach their children that violence against women is always wrong.”

Call me a starry-eyed optimist, but I have long been convinced that there are millions of men in our society who are ready to respond well to a positive message about this subject. If you go to a group of men with your finger pointed (“Stop treating women so badly!”) you’ll often get a defensive response. But if you approach the same group of men by appealing, in Abraham Lincoln’s famous words, to “the better angels of their nature,” surprising numbers of them will rise to the occasion.

For me, this is not just an article of faith. Our society has made real progress in confronting the long-standing problem of men’s violence against women just in my lifetime. Take the 1994 Violence Against Women Act (VAWA). It is the most far-reaching piece of legislation ever on the subject. Federal funds have enabled all sorts of new initiatives, including prevention efforts that target men and boys. There have been many other encouraging developments on both the institutional and the individual levels. Not the least of these positive developments is the fact that so many young men today “get” the concept of gender equality—and are actively working against men’s violence.

I understand the skepticism of women who for years have been frustrated by men’s complacency about something as basic as a woman’s right to live free from the threat of violence. But I am convinced that men who are active in gender-violence prevention today speak for a much larger number of men. I would not go so far as to say that a silent majority of men supports everything that gender-violence prevention activists stand for, but an awful lot of men privately cheer us on. I have long felt this way, but now there is a growing body of research—in social norms theory—that confirms it empirically.

Social norms theory begins with the premise that people often misperceive the extent to which their peers hold certain attitudes or participate in certain behaviors. In the absence of accurate knowledge, they are more likely to be influenced by what they think people think and do, rather than what they actually think and do. Some of the early work in social norms theory, in the early 1990s, had to do with how the drinking habits of college students were influenced by how much they thought their peers drank. Researchers found that when students realized that their fellow students didn’t drink as much as their school’s “party school” label suggested, they were less likely to binge drink in order to measure up.

Social norms theory has also been applied to men’s attitudes about sexism, sex, and men’s violence against women. There have been a number of studies in the past several years that demonstrate that significant numbers of men are uncomfortable with the way some of their male peers talk about and treat women. But since few men in our society have dared to talk publicly about such matters, many men think they are the only ones who feel uncomfortable. Because they feel isolated and alone in their discomfort, they do not say anything. Their silence, in turn, simply reinforces the false perception that few men are uncomfortable with sexist attitudes and behaviors. It is a vicious cycle that keeps a lot of caring men silent.

I meet men all the time who thank me—or my fellow activists and colleagues—for publicly taking on the subject of men’s violence. I frequently meet men who are receptive to the paradigm-shifting idea that men’s violence against women has to be understood as a men’s issue, as their issue. These men come from every demographic and geographic category. They include thousands of men who would not fit neatly into simplistic stereotypes about the kind of man who would be involved in “that touchy-feely stuff.”

Still, it is an uphill fight. Truly lasting change is only going to happen as new generations of women come of age and demand equal treatment with men in every realm, and new generations of men work with them to reject the sexist attitudes and behaviors of their predecessors. This will take decades, and the outcome is hardly predetermined. But along with tens of thousands of activist women and men who continue to fight the good fight, I believe that it is possible to achieve something much closer to gender equality, and a dramatic reduction in the level of men’s violence against women, both here and around the world. And there is a lot at stake. If sexism and violence against women do not subside considerably in the twenty-first century, it will not just be bad news for women. It will also say something truly ugly and tragic about the future of our species.

WOMEN’S ISSUES/MEN’S ISSUES

If you are a woman and you are reading this, you know that violence against women is one of the critical “women’s issues” of our time. A major national poll released in 2003 by the New York-based Center for the Advancement of Women found that 92 percent of women named “reducing domestic violence and sexual assault” as a top priority for women’s movements—outpolling all other issues.

If you are a man and you are reading this, you probably agree that violence against women is a significant problem—for women. Few men tell pollsters that “reducing domestic and sexual violence” is a priority for men. Barring a recent family tragedy, it is unlikely that men would even register these issues as ones we should be concerned with. This hardly ennobles us, but is it fair to expect otherwise? Most men—and women—see these as “women’s issues.”

As I have stated, calling violence against women a “women’s issue” is misleading at best, and is even at some level dishonest. In fact, I think the very act of calling it a “women’s issue” is itself part of the problem. Here are four reasons why:

1. It gives men an excuse not to pay attention.

The way we talk about a subject is the way we think about it. When people call rape, battering, and sexual harassment “women’s issues”—and many people do this without a second thought—they contribute to a broad shifting of responsibility from the male perpetrators of violence to its female victims. This is likely not intentional, but words nonetheless convey subtle but powerful messages. The message to women is that it is their job to prevent—or avoid—sexual and domestic v

iolence, and they should not expect a lot of help from men. The message to men is even more insidious: they need not tune this in. It is women’s burden. As long as you do not assault women yourself, you can pretty much ignore the whole thing.

The simple phrase “women’s issues” eloquently reinforces this point. Guys hear “women’s issues” and not surprisingly think: Hey, that’s stuff’s for girls, for women. I’m not a girl or a woman. It’s not my concern. Generations of men and boys have been conditioned to think about sexism—including gender violence—as something they need only concern themselves with when forced to do so, usually by a woman in their life.

When did you last hear a man say he was concerned about violence against women not in spite of the fact that he is a man but because of it? Implicit in the notion that violence against women is a “women’s issue” is the assumption that all women should be concerned because they’re women, because all women have an interest in preventing violence against their sex, even if they haven’t been assaulted themselves. It is equally true that men should be concerned, not necessarily because they have perpetrated or prosecuted these crimes, but simply because they are men.

Macho Paradox: Why Some Men Hurt Women and and How All Men Can Help

Macho Paradox: Why Some Men Hurt Women and and How All Men Can Help